Posted on 08 Feb 2024

Targeting Net Zero

Over the last few years, climate change efforts have accelerated. ASEAN-6 countries have announced net zero targets (except the Philippines).

Most ASEAN-6 countries have been introducing climate change related legislation, further demonstrating their commitment to decarbonizing the entire economy.

The steel industry has been identified as one of the heavy emitters of greenhouse gases (~7% of global emissions). Hard-to-abate, the steel industry, especially in ASEAN, faces many challenges in efforts to decarbonize.

Challenges in Decarbonisation

The ASEAN-6 steel industry faces many major challenges in the effort to decarbonise, and to date, there is no clear solution that is immediately on hand, to implement effectively.

Overcapacity & Overinvestment

The ASEAN region is attracting many steel investments, creating an overcapacity crisis.

From a crude steel capacity of 75.3 million tonnes in 2021, the region is expecting to add more than 76.6 million tonnes, pushing capacity to about 151.9 million tonnes before 2030. However, we also found out that there are additional 19.9 million tonnes of new projects being planned in Vietnam and this will take the final capacity to 171.8 million tonnes in the future.

Note that ASEAN’s finish steel demand was only about 75 million tonnes in the last 2 years and growth has been sluggish of late.

Severe overcapacity leads to severe competition, massive exports, financial losses and the industry’s eventual inability to invest for the future.

De-Greening of the Industry

Most of the new upstream steel projects are based on blast furnace / basic oxygen furnace (BF/BOF) systems. This is leading to a major shift from Electric Arc Furnace (EAF) systems which was the dominant technology used before 2014.

The ratio of BOF to EAF capacity was 5%:95% in 2011. The ratio became 34%:64% in 2021, and is projected to rise to 61%:39%. The shift to BF/BOF system is increasing the carbon intensity of the ASEAN steel industry in the future.

The latest BF/BOF investments are at most 10 years old and are “not ready” for a major upgrade, risking these to become unprofitable and may become stranded assets once carbon tax or other climate change legislation comes into effect.

No Commercially Proven Green Technology

The hydrogen council estimates that use of green hydrogen, which utilises renewable energy, will be feasible by the mid-2030s (i.e. ~2035).

Now, only grey hydrogen (based in fossil fuels) and natural gas are available and these are feasible for use, even though they are carbon intensive.

The next stage after grey hydrogen is blue hydrogen, which requires Carbon Capture, Utilisation and Storage (CCUS) technologies to decarbonise. However, CCUS technology is also not yet commercially viable and is another probably 4-5 years away.

Pursuing all these technologies today will be very expensive and unaffordable. Even when all these technologies become commercially viable, they may be proprietary and not be accessible by the industry players. Even when these do become accessible, there would be a rush to acquire these technologies or hydrogen, that there may not be sufficient supply for everyone for some time.

Carbon Tax and Carbon Leakage

Many countries in Europe have introduced carbon tax with varying rates by country from as low as €0.07 (USD 0.08) in Poland to as high as €116.33 (USD 137) per tonne of CO2 equivalent (/tCO2e).

Similarly, Singapore has introduced a flat carbon tax across all industries in 2019. Starting at SGD 5/tCO2e, this will rise to SGD 25/tCO2e in 2024z, to SGD 45/tCO2e in 2026 and eventually to around SGD 50-80/tCO2e in 2030. Other ASEAN countries are expected to introduce carbon tax soon and carbon tax will become a burden to the ASEAN steel industry.

While carbon tax is expected to accelerate the efforts for the industry to decarbonise, it also puts the local industry at a disadvantage against imports that do not have to pay carbon tax. This is carbon leakage and it comes from carbon intensive imports or from companies moving production to countries with lower emission standards to avoid carbon costs.

Considering that ~60-70% of ASEAN’s finished steel demand comes from imports, the risk of carbon leakage into ASEAN is high.

Europe’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism

The European Union introduced Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) to prevent carbon leakage; this will take effect from 2026, Indonesia, Malaysia and Vietnam export sizeable quantities of raw materials and steel products to Europe and these will be more expensive due to CBAM.

It is also expected that other countries may follow suit with their own version of CBAM to reduce potential carbon leakage into their countries.

No Clear Standards, Direction & Policies

While many ASEAN countries have committed to net zero targets, it is still not clear how some of the countries are going to meet those targets. Policies are being formulated and legislations are expected to be introduced over the next couple of years.

Furthermore, there is a need to clearly define what is green steel and to have a unified standard on carbon accounting, measurement, reporting & validation. Similarly, as a global effort to decarbonise, carbon exchanges should be interlinked to allow seamless trading across the world.

While decarbonisation of the supply side is underway, there is also the issue on how to get the market to accept green products. Decarbonisation will increase cost of green products and services. The question is, would the end consumers be willing to pay for this? Would countries with portions of population at the poverty level be able to afford green products?

Potential Scarcity of Raw Materials

Among the technologies that are being touted as low carbon steel making is the use of a Direct Reduced Iron system with the EAF. For this to work, key raw materials such as iron ore and scrap are needed.

According to Midrex, the quality requirements of iron ore for direct reduction are well known and will not be detailed here, but are in essence:

Furthermore, iron ore quality has deteriorated progressively over the last 2 decades. While, the quality of seaborne iron ore pellets and DR grade pellets have remained constant, the proportion of high-grade iron ore with > 67% Fe is relatively small.

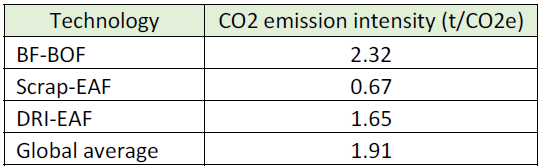

The EAF is the cleanest and greenest technology to produce steel, according to Worldsteel Association benchmark values (table 1 below).

Table 1: CO2 Emission Intensity by Production Route

Because of that many countries are introducing policies to encourage the shift towards using EAFs. EAF’s require scrap. However, scrap can also be used in BF/BOF. Since the use of scrap helps to decarbonise the steel industry, many countries (including Germany and the European Union) are dependent on the availability of scrap as raw materials.

China’s Hebei Province, for example, has called for the industry to increase scrap recycling capacity to more than 22 million tonnes per year by 2025 and for EAF share to become 10% of capacity by 2050 and 15% by 2030. This province produces 211.9 million tonnes of steel (~90% using BF/BOF).

As at September 2023, more than 60 countries have either banned or are in the process of banning scrap exports. With many countries looking at how to use more higher purity iron ore and scrap, there is a major concern about the shortage of these essential raw materials.

Current Economic Situation

According to World Bank, in their June 2023 forecast, global economy is expected to slow down to 2.1% amid continuing monetary policy tightening to control high inflation. 2024 recovery will be tepid at 2.4%. Tight global financial conditions and subdued external demand are expected to affect growth across emerging market and developing economies.

Current economic situation affects business and hamper efforts and investments into decarbonisation.

Policies to Help Transition to Low Carbon Future

As much as the steel industry (or any other industries) want to decarbonise, there is very little anyone can achieve in big leaps today. Many efforts on developing technologies for production of green hydrogen, production of green steel, CCUS technologies, generation of green energy are still at early stages.

Because of economic reasons to both the industry and consumers, it is essential that policy makers provide incentives for all stakeholders to move to a low carbon future.

So, what factors should be considered for policy interventions to help the steel industry to transition to a low carbon future in ASEAN?

Investment Policies

To tackle the issue of overinvestment and overcapacity:

On the de-greening of ASEAN steel industry

ASEAN Regional / National CBAM

If carbon tax is further introduced in ASEAN (other than Singapore), there will be carbon leakage from imports. Therefore:

Scarcity of Raw Materials

Policy intervention for raw materials is trickier as it depends on the availability of local scrap. Many countries are banning or in the process of banning the export of scrap so they have sufficient green raw materials locally.

As for the development of new sources of green raw materials for steelmaking such as DRI/HBI:

Market Development Policies

More than the focus on de-greening of the supply side, there is a need for market development policies to encourage use of green materials such as green steel. Some examples are:

There are of course many other potential ways to incentivise the use of green products either through monetary or non-monetary ways.

Access to Technologies & Financing for Transition

Green technologies needed for decarbonisation is going to be expensive. As innovations happen, these are going to be mostly proprietary and not accessible. So how can developing countries be able to afford or to even get access to such technologies?

There have been calls for rich countries to fund poor countries to help them transition to a low carbon future. Rich (or advanced) countries have benefitted from polluting the world for a long time and have bigger carbon footprint than developing countries.

The US’s inflation reduction act (IRA) and Europe’s green deal for example, are expected to fund the development of decarbonisation technologies. Advanced countries could require:

There could be other mechanism to help the global climate change efforts.

At the same time, multilateral development banks such as the International Finance Corporation (IFC) and the Asian Development Bank (ADB) should allocate more funds to help developing countries as well as industries, such as the steel industry with decarbonisation.

There is also a need for regional / local banks to help regional / local companies transition towards a greener future and they should not shut off financing to hard-to-abate industries such as the steel, cement, aluminium or other carbon intensive industries.

These are only some of the areas that SEAISI has covered. The journey towards a green future is full of uncertainties and along this journey, there will be challenges and surprises. So, let’s stay united and help each other to help the world become greener, better and more liveable for all.

Should you have any other ideas or feedback, please reach out to the Secretary General at seaisi@seaisi.org.

Stay Healthy. Stay Safe.

See You at SEAISI Events.

Source:SEAISI